Tuesday, January 28, 2014

Your California Dive Bar Jukebox Song of the Week

The Count Five, from San Jose, are the archetypal mid-60's garage rock

'n roll story. Five California suburban teenagers who picked up

instruments trying to sound like British rockers who were

trying to sound like black Southern blues men and then coming up with

something new, raw and in it's own genre we now call garage rock.

Hardly before the band even had a name "Psychotic Reaction" was a hit

song in 1966 and the band was signed to a record label who rushed them

into the studio to quickly write and record an album full of mediocre

songs that were not nearly on the level of their single. By early 1968,

the members of The Count Five wisely decided going college was a better

bet than to vainly pursue rock stardom and they called it quits. If

not for being preserved in the memory of true and great record geeks

like critic Lester Bangs and Lenny Kaye, who compiled the Nuggets

compilations of garage rock, the Count Five would have been lost to

history and never passed to the younger generations of record geeks like

myself.

Saturday, January 25, 2014

Skies Blackened With Swallows- The Swallow's Inn Saloon, San Juan Capistrano

This written script is pretty loose, so I highly suggest you download this episode by clicking on the red star to the right or from iTunes. While in iTunes, don't forget to to give a review of the show. However, this post is still worth taking a glance at because I posted plenty of pretty pictures and some useful links. Enjoy!

I’m

sitting on the back patio of the first bar I can remember ever being aware

of. I can still remember passing

by this Swallow’s Inn Saloon, with its weathered brick façade, iron bars over

the windows, Old West style batwing doors. It’s the image of the doorway that really stayed with me

because the darkness of it seemed to absorb the bright afternoon light. Downtown San Juan Capistrano glistens

in the sun, with red brick and wood and yellow adobe buildings, the result of

careful preservation, so maintained people might catch a glimpse of the small

and lackadaisical town that was at the forefront of the ambitious California

Mission experiment. But the shadowy

door to this saloon… the darkness seemed to emit from the bar and felt intentional

to me, as way of keeping kids like me from seeing what was inside, but it

ceaselessly spilled out the raucous voices of men and guitar heavy rock and roll

from some jukebox deep inside.

Unlike our friend, Jack London, I did not grow up going into bars. My parents and their friends drank, but at eight years old,

the idea of place where people gathered for the sole purpose of drinking

alcohol seemed crazy and dangerous to me, as if every person in there must be

absolutely hammered and the scene must be something similar to an insane

asylum.

It felt like there

were only a handful of bars in South Orange County in the early 1980s and the

only one anybody talked about was the Swallows. Today Southern California is notorious for the continuous

metropolis that solidly blankets the land between the Mexican border to the San

Gabriel Mountains, north of Los Angeles, only punctured by the Marine Base,

Camp Pendleton in north San Diego County.

But in the early 80s that blanket was more like a net, with spaces

alternating between suburban towns with tract houses and shopping centers and

then ranch land and citrus groves, sometimes even some wild spaces where native

chaparral planets still dominated the landscape and hid coyotes and mountain

lions. To be sure that net was tightening in those days, but I can remember

hearing cows mooing on quite nights from a once grassy open field that has been

a supermarket for near thirty years now.

Sitting here, at

this bar that so mystified me as a kid, I’m getting nostalgic for what I would

call a simpler time, if I did not know it only seemed so because it was seen

through the eyes of a child. This

kind of nostalgia is aided by the fact I’m near the bottom of my second gin and

tonic, and as soon as I finish I’m going to walk over to do the tour of Mission

San Juan Capistrano. Growing

up only a few miles from here meant multiple elementary school fieldtrips to the

Mission, where we were told of the Franciscan friars who were the first white

residents of California. Those

tales largely painted a heroic picture of the missionaries, who were said to

have lived in peace with the local Indians and prepared those people for modern

world that would soon wash up with the waves of the Pacific. But there were hints from our teachers

and tour guides that the Franciscan story was perhaps more complex and ugly

than they were ready to tell us.

After all, this was group of educators who came of age in the 1960s and

70s, in which various civil rights movements complicated how white Americans viewed

history, forcing a recognition that nobody was served by ignoring the

historical perspectives of subjugated minorities. But what should they have told us, elementary school

kids who were still naïve enough to envision bars as akin to mental

institutions? Should they have

told us the Indians at the Mission were not allowed to leave, and were forced

to work in slave like conditions?

Or how those people were whipped as punishment? Of imprisoning natives until they

converted to Christianity? Lord

knows, those types of salacious details would have seized our attention. And all this would have been true, but

only part. That certainly would

have cemented the idea in our little heads that the friars were purely villains

and the natives were purely victims.

Which was not the truth, and I suggest at this mischaracterization of

history would be more false and more damaging than the whitewashed story we

were given. Painting with a broad

brush and labeling good guys and bad guys, oppressors and victims, removes the all

motivations of real people and does nothing to explain why things happened as

they did. We do not teach history

so that our children can judge the past, but so that they can better understand

the world they live in today. There

is no such thing, nor as there ever been, as a simpler time.

Alight, this drink

is dusted. It’s time for me to see

the Mission through adult eyes.

We’re at the Swallow’s Inn Saloon in San Juan Capistrano. And this is the Bear Flag Libation.

On

July 23, 1769, Gaspar de Portolá entered the valley they dubbed Santa Maria

Magdalena, which would include part of today’s Capo Beach, Dana Point and San

Juan Capistrano. Portola’s party

of about sixty-five men, including Father Juan Crespi, was only nine days into

their march from San Diego to Monterey with the intent to explore and assess

the roughly 450 mile long land route between those tiny outposts. Spain had made claims to this part of

the world since Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo discovered the San Diego Bay in 1542, but

in two hundred years Spain made slow progress in actually moving into, or even

checking out, this sliver of their massive New World empire. For quite some time because of the length

of the gulf between what is today mainland Mexico and the Baja California

Peninsula, people assumed the whole of California was one long island. In fact, the name California is thought

to derive from a Spanish romance novel Las

Sergas de Esplandián, which contains this passage, “Know that on the right

hand from the Indies exists an island called California very close to a side of the Earthly Paradise; and it was

populated by black women, without any man existing there, because they lived in

the way of the Amazons. They had beautiful and robust bodies, and were brave

and very strong. Their island was the strongest of the World, with its cliffs

and rocky shores. Their weapons were golden and so were the harnesses of the

wild beasts that they were accustomed to domesticate and ride, because there

was no other metal in the island than gold.” Now, records of Cabrillo’s voyage have long been lost to

time, so we can’t be sure what was in his mind when giving the name, and we

can’t even be sure it was Cabrillo who gave the name- obviously he did not meet

the legendary queen, Califia, which

modern scholars have deduced is likely to have been the Spanish word for a

female Islamic leader, like a Caliph- so we don’t know if he actually believed

he found this mythical land or if he simply thought the name applied. At the time Cabrillo would have believed

he was much closer to Asia than he actually was, but he was in a paradise-like

land of coastal cliffs and rocky shores, at the left hand of Asia. He would never know how apt the name

was, with the richest gold deposits in the world waiting to be discovered beneath

the California mountains, and how, it is a known fact, the most beautiful women

in the world would forever grace these lands. So, good residents of California, if you’ve ever wondered

where the name of your home comes from, the best guess of scholars is that a Portuguese

explorer believed he found an Islamic island of Amazon women from a Spanish

romance novel. But who knows? The guy slipped on a rock a short time

later, got gangrene and died, then somebody lost journal. Such is life and history.[1]

Before

we get back to Portola’s Expedition, I feel I should point out that we’re about

to cover some sixty plus years of history in about an hour. There are entire courses that teach only

the Spanish and Mexican eras in California and still only scratch the surface,

so by no means am I meaning to give a comprehensive history of the Missions, or

of San Juan Capistrano, or even the Swallow’s Inn for that matter. This will be a crash course in

some things I find interesting in all three and I encourage you to dig deeper

on any points you find interesting.

The narrative will center around San Juan Capistrano, but California

then, as it is now, carried remarkable diversity among its the native people. It is thought that at the time the

Missions were first being built that there was as

many as 500 of different tribeletes and more than 100 separate language groups

spread out across this incredibly large area. Historian Kevin Starr asserts that nearly a third of the

native people, who lived in the area that became the United States, lived in

California, the number being somewhere around 300,000.[2]

Before

we get back to Portola’s Expedition, I feel I should point out that we’re about

to cover some sixty plus years of history in about an hour. There are entire courses that teach only

the Spanish and Mexican eras in California and still only scratch the surface,

so by no means am I meaning to give a comprehensive history of the Missions, or

of San Juan Capistrano, or even the Swallow’s Inn for that matter. This will be a crash course in

some things I find interesting in all three and I encourage you to dig deeper

on any points you find interesting.

The narrative will center around San Juan Capistrano, but California

then, as it is now, carried remarkable diversity among its the native people. It is thought that at the time the

Missions were first being built that there was as

many as 500 of different tribeletes and more than 100 separate language groups

spread out across this incredibly large area. Historian Kevin Starr asserts that nearly a third of the

native people, who lived in the area that became the United States, lived in

California, the number being somewhere around 300,000.[2]

Aside from their own cultural differences, each tribe

responded to arrival of the Spanish differently and obviously the Europeans

were not monolithic either. Some

were criminals serving their sentence with military duty, some were godly men

on what they believed a holy mission, some of the former acted with honor and

kindness, some of the latter lost their way and acted with cruelty. Every encounter shaped future relations. It always boggles my mind to

contemplate that when two disparate cultures, that somebody might have had a

cold or a hangover and suddenly a reputation for laziness or foul tempers gets

applied to a whole group for decades.

Things like rigid dogma or

warrior traditions cannot always be blamed for a culture clash. One frightened young man who

misinterprets a move to be hostile and acts with hasty violence can start a war

of bloody reprisals. One curious

soul can avert war and make lasting friendships by simply walking up and

saying, “Hi, I’m Bob. Boy, that’s

a shiny helmet you got there. You

guys want to come have some dinner?” Such is life and history.

With

that said, when Gaspar de Portolá’s expedition came into what is today

South Orange County they had contact with a number of villages and all of who

came out to meet them were friendly.

Fray Juan Crispi described them thusly, “They came without arms, and

with a friendliness unequaled; they made us presents of their poor seeds, and we

made return with ribbons and gew-gaws. Nearly the whole day they remained with

us, men, women and children; and these heathens listened with more attention to

what we told them by signs, of God, of Jesus Christ, and of their salvation,

and several times they devoutly venerated the Holy Christ and the cross of the

crown.” Considering there was not

a single person present who could even remotely guess at the language of the

others, I’m going to go out on a limb and say it’s unlikely they communicated

all the portentous significance of Jewish carpenters who won’t stay dead. If they had, the mere fact that all these

bearded and armored strangers all wore symbols of the 1800-year-old torture and

execution of their god and savior, might have been a tip off the new guys have

some violent tendencies. It’s

likely Crispi saw what he hoped for, which was the Franciscan’s long-term goal

of potential conversions. Portola,

ever the soldier, simply wrote of that meeting: “they made us a present of much

grain and we made them a suitable return. We rested for one day.”[3]

Europeans

intermittently passed through this area for the next six years as six missions were

built between San Diego and San Francisco. In 1775, Father Junipero Serra, Father Presidente of the

Franciscan order in California, planned on building a mission in San

Buenaventura, in modern Ventura, north of Los Angeles, but plans were postponed

due to hostile natives attacking the Spanish incursions on their land. Instead, he authorized to build one

near San Juan Creek, which he dubbed San Juan Capistrano, named after an Italian

saint and Franciscan who led soldiers into the battle that lifted the Ottoman

Siege of Belgrade in the fifteenth century. Now, I’ve been throwing around the terms Franciscan

and missions pretty liberally thus far, but who were these cats and why were

they erecting walled churches out in the middle of the California wilderness?[4]

Back in the episode

zero I referred to the Spanish method of colonization as being something more complex

than the occupation and repopulation of a new area; they didn’t just want new

lands for Spain, they wanted new and loyal Spanish subjects. But how do they go about taking these

perfectly content native people of the wild Americas and turn them into fruitful

Spaniards? You can’t just show up in

somewhere like Peru and say, “Okay, guys, you work for us now. So if you’d kindly put down that spear

your pointing at me, pick up this pickax, yeah, here ya go, and why don’t you

just start mining that mountain here. Here’s a guidebook on how to be Spanish, read it all by

Tuesday and we’ll be back to take the fruits of all your labor back to a single

man who you’ll never meet and who lives across the ocean. Muchas gracias, amigo.” No, there had to be incentives. Obviously, the Spanish had a pretty

sturdy stick in their military superiority, but the invasion into the interior

of Mexico was a blood bath that nobody was eager to repeat. What kind of carrot can go with that

stick? (snap) “Hey, how does an

eternal and blissful afterlife sound to you? Yeah, this shit is pretty dope.” It turns out they did have a guidebook on how to be Spanish:

it was called the Bible.

A pretty clever

plan for colonization was established called the Laws of the Indies, which was basically

a three-prong strategy. First,

there would be the church to preach the Good Word to the natives, bring them

into the fold by teaching them not just about Jesus Christ, but how to read,

about hieratical institutions and to practice trades that would be useful in

Spanish society. The missions were

simply the physical manifestation of this project. Life was centered around the church building and a mass

schedule, but they missions served a whole community inside and outside their

walls that produced most of the actual food and items people there needed to

live. Most, as is the case of the

San Juan Capistrano Mission, had barracks, farms, forges, blacksmiths, and stables. The second prong was the military forts

to defend the churches, put down uprisings and protect the colonies from

encroaching European powers. Think

of the Presidio in San Francisco. When

it was built in 1776, it was the northern most outpost of the Spanish Empire

and stood guard, facing the Russian settlements in the north bay, who were

really more fur trappers than a military presence. Still, doesn’t hurt to point a couple cannons at them, just

to show them Ruskies you mean business.

And finally, there was the pueblo, towns to serve as centers of trade

and teach the natives of Spanish secular culture. So there you have it, the Laws of the Indies: mission,

presidio and pueblo; religion, military and economics- all the driving forces

of the Spanish Empire. Under this

perfect tutelage, well even the most backward of people would be near indistinguishable

from citizens of Madrid in just a few short years. Ten years in fact.

When Junipero Serra came to California he estimated that in a mere

decade the Franciscans would have the natives converted, sworn frailty to the

king of Spain and not just running the place, but converting natives on their

own and expanding the glory of the Empire themselves. Serra only missed his optimistic ten-year goal by… entirety,

as no such thing came even close to happening. In Alta California the strongest presence was definitely the

Missions. Often pueblos failed or

were never built and only four real presidios were constructed, in San Diego,

San Francisco, Monterey and Santa Barbara, contrasted to the twenty-one

missions that were eventually erected.

|

| Misión de Nuestra Señora de Loreto Conchó |

With the Jesuits

gone, there became a need for a new order to head up the religious prong of the

three-prong system. Catholic

missionaries were the prefect colonists because their whole purpose for being

was to meet new peoples and convert them, but Carlos III needed people who

acted in Spain’s interest. Enter

the Franciscans into California.

The Franciscan Order did not have in-house resources of the Jesuits and

were instead reliant on charity and benefactors to do their proselytizing. They were disciples of St. Francis of

Assai- austere and humble to the point of asceticism, devoted to keeping a mind

and heart spiritually detached while the body suffers and works tirelessly, and

when the rubber hit the road, they were some serious dudes to be out there

converting Indians. By all

accounts, as a group, there is no questioning their compassion for the people

they hoped to convert and true in their belief that they were helping the

neophytes- which is the term for the converted natives who lived at the

Missions- but people who’s faith commands to them to treat themselves severely

are likely to be sever in teaching other people that faith.

In 1768, after handing

the Baja California missions over to the Franciscans, the Spanish Crown

authorized them to expand into Alta California. The Spanish government fully funded this enterprise, giving

the Franciscans the directive to rapidly expand into as much territory as they

could hold. As far as the

Crown was concerned the Franciscans were mainly placeholders. Let these religious types go out

and convert as many people as possible, but essentially they were solidifying

the Spanish claim to the land, which could be better colonized later. The Franciscans were concerned with

saving the souls of the heathens of California, but were not ignorant of the

government’s plans and part of their mission was to prepare the native people for

the oncoming storm. It was only a

matter of time before hordes of Europeans descended upon these gorgeous shores

to exploit the rich resources.

There would no place in this new order for the naked and godless who

hunted and gathered, they must be prepared, speak the language of the new

comers, know some trades that allowed them to thrive in the new society. The hope was that by the time the hordes

arrived the natives would already be living in the Spanish mode, thus able to

retain a high status in their ancestral land. So, by contrast, unlike the majority of Americans and

English, who saw the Indians as enemies who were unable to assimilate to a

European culture, the Franciscans never saw the natives as their enemies. The enemy they believed they fought was

Satan, who manifested himself in the native’s heathen practices and stood in

the way of their ultimate survival.[6]

To this end, the padres often

lured natives to the missions with exotic gifts and abundant food. According to Father Palou in San Juan Capistrano, most

natives there came quite freely with the simple promise of baptism. In fact, they could not build housing

fast enough for all the neophytes flocking the Mission. From the perspective of the natives the

padres must have an irresistible curiosity, something not unlike aliens

landing. Not only did they have so

much, but they wanted to teach the natives how to produce that kind of wealth as

well. The catch was that after the

natives became neophytes, they were not allowed to leave the missions and the

friars controlled every aspect of their lives, from what they ate for breakfast

to who they were allowed to marry.

This surely came as a shock to the people who had no concept of

imprisonment, especially when soldiers tracked down any runaways and brought

them back to the mission. Further,

the

Franciscans viewed a forced conversion under threat of death or imprisonment to

be count as just the same spiritual victory as a voluntary one. In an article by historian Russell Skowronek on the Ohlone Indians at the missions in the Northern California,

an English geographer named Frederick William Beechy

in 1826 described soldiers going out to round up Ohlone women and children, at

which point the men would simply follow their families to the mission and, “voluntarily follow them into captivity. After capture they are taught in

Spanish the Lord's Prayer and how to cross themselves.... If they show a

repugnance to conversion they are imprisoned for a few days and then let out

for fresh air and to observe the happy mode of life of their converted

countrymen.... Their incarceration ends when they are willing to submit. It usually didn't take long… as

the Indians adverse confinement [who isn't?] that they very soon become

impressed with the manifestly superior and more comfortable mode of life of

those who are at liberty… They then are trained in a trade.” Men were trained as cowboys, farmers,

shepherds, blacksmiths, shoemakers, stonemasons, carpenters and butchers. Women were trained to do things like

weave, sew, wash, make baskets, cull wheat, sift flour, grind and hoe weeds.[7]

The padres were

clearly deluding themselves to the benefits they provided the neophytes. One friar wrote in a letter, “For one who has not seen it, it is impossible to

form an idea of the attachment of these poor creatures for the forest. There

they are without a roof, without shade, without food, without medicine, and

without any help. Here they have all of these things to their hearts content.

Here the number who die is much less than there. They see all this, and yet

they yearn for the forest.” Putting

aside the ethnocentric ignorance in this statement, which more less the stance

of all Europeans of the era, this friar was just plain wrong about the longer

and better lives enjoyed at the mission. Skowronek details archeological evidence to support that the

neophytes were in fact overworked, undernourished and highly susceptible to all

the disease the friars and soldiers inadvertently brought with them from the

Old World. Unfortunately, like in many

places in the Americas, once tribes became dependent on European agriculture

and goods, their old ways were abandoned and skills for surviving in the

wilderness atrophied. Many natives

feared the Spanish and moved east, well out of reach of the invaders, but those

who stayed were, both directly and indirectly, found themselves ever linked to

the Mission system.[8]

|

| Color version of Louis Choris' drawing of Presidio San Francisco |

One of the most controversial

aspect to the Franciscan-neophyte relationship has long been the use of

whips. The degree to which natives

actually volunteered to become neophytes is somewhat murky, but when they

started whipping those they claimed to protect the Franciscans begin to look at

lot like slavers. Junipero Serra

has been on the short list for sainthood by the Catholic Church for a very long

time, but when native groups protest the canonization of somebody who

terrorized their ancestors, the evidence of men of the cloth inflicting

corporal punishment is all too available.

Historian Edward D. Castillo flatly indicts the Mission system as

“authoritarian institutions whose foundation rested on military occupation and

forced labor.” In the journal California History, Castillo reproduced

a circa 1816 painting depicting natives being herded to work by soldiers with pikes,

which is disturbing enough, but the bulk of his article is a translation of an

interview with the son of one of the men who assassinated Father Andrés

Quintana at Mission Santa Cruz in 1812.

Quintana’s reputation for wanton cruelty was widely known to the natives

throughout California and even many Spanish thought the man went too far. Apparently, he delighted in crafting

new whips out of wire and iron that could more easily rip the skin off people’s

backs and he tested his creations on his flock, often without even the pretense

of a crime. Castillo also points

to some insinuations that Quintana may have sexually abused some of the young

women. Understandably, a group of the

neophytes in Santa Cruz decided the only way to escape this malevolence was to murder

the man. After a series of ruses that each resulted in the plotters

loosing their nerve, they eventually cornered the father while he was isolated

and strangled him with his cape. A

poor plan went worse when they checked on his body later found the man coming

to, surely ready to speak of his assault. Wanting to leave as few signs of foul play as possible, they

decided finish the man off by crushing his testicles. I had never heard of this as a method

for murder, but this is the story one of the conspirators told his son. I googled it up and apparently the

crushing of these internal organ can send a man into a type of neurogenic shock, which can be fatal. Oh, and by the way: ouch.

Like, seriously, yo. Ouch.

In the case of Quintana, the neophytes got away with it, it would seem

to a lucky chance that the local surgeon who preformed the autopsy was either

ridiculously negligent or sympathetic to the plight of the abused

neophytes. Those who mourned the

dead sadist generally accepted Quintana’s death to be a natural one and the

truth did not come out until years later, when two native women discussed the

matter near a Hispanic man who they did not realize spoke their language.[9]

|

| Farther Andres Quintana |

Obviously this does not excuse,

but it helps explain a bit of why the Franciscans felt it okay to inflict

corporal punishment. Francis Guest points out that in most parts of the

world at this time, definitely including Spain, whipping children was seen as

how you raised children. It was right there in the bible, Proverbs 13:24,

“He who withholds his rod hates his son, But he who loves him disciplines him

diligently.” These men were whipped as children, if they were not priests

and had children of their own, they would have whipped them. Further, the

Franciscans were ascetics, who often whipped themselves. Mostly not to a

freaky sadomasochistic degree like the crazy giant albino in the Da Vinci Code, but the deprivation of

the body was a way of bringing the spirit closer to God. Finally, the Spanish did not send anywhere

near the manpower and resources to come in and build a system that resembled

the American antebellum South, even if they had wanted to, so if excessive

brutality had been widespread the Mission system would have immediately been

overrun. In large part, the neophytes

did not view the missions as source of oppression, as most stayed in and around

the missions and remained deeply Catholic long after the missions became

defunct. In San Juan Capistrano,

the Indians only left the mission after decades of neglect and exploitation that

came with secularization in the Mexican Era.[11]

So with all this in mind, I find

the California Missions quite unique.

The Franciscans and their soldiers came to California and coaxed the

natives to the Missions. Sometimes

this was done with friendship, sometimes through bribery, sometimes through

deception, sometimes through violence.

At this time the native people lost their freedom and were put to work

under harsh conditions under the threat of gun, blade and whip. By this description, it has all the

signs of slavery. But then let’s

consider the motivations: the majority of neophytes came of their own volition

and escape was by no means impossible. No goods were produced in the Missions that were not used by

the Missions, so there was no economic gain for anybody in this system. The Spanish Crown only benefited in

that their claim to the region was being held, they were making an investment

toward a future colonization effort.

The Franciscans only ever saw themselves as stewards to the land, their

sole purpose for being in California was to, in their minds, save souls and

prepare the natives for future.

So, what I say this was unique, I ask when else in human history has a

slave system been established for the express benefit of the slave? Sure, we know now that the next wave of

Spanish colonization would never come, they lost Nueva España before that could

happen, so we may deem the Franciscan effort as misguided and ultimately a

failure, but what if things had gone according to plan? If the Mexico did not gain

independence, the Americans were not yet ready to take on the Spanish Empire

and would not have annexed California, the Franciscans ended up fostering new generations

of mixed race people who eventually discovered the vast amounts of gold buried

beneath the Sierra Nevadas and world flocked to California with a Spanish Gold

Rush and with the one-time neophytes having a head start. I find this an unlikely course for

history to have taken, but not entirely implausible one. So should the stated altruism of the

Franciscans effect how we look their questionable means? I do not ask this to excuse the uprooting

of the native way of life, nor am I defending the abuses that followed, but so

we can look at this period of history not simply see abusers and victims, or

some kind of cogs in the colonial machine that chewed up natives people in the

name of European progress, but they were real people, with real agency, making

choices: grand and small, selfish and selfless, knowledgeable and ignorant,

sometimes getting the results they aimed for, sometimes losing everything.

Okay, are you ready to finally

settle into to San Juan? Let’s

properly introduce the town, mission and bar they way to world was introduced

to it: with the migration patterns of a tiny bird.

In the 1930, Father John St.

O’Sullivan, the man who made his life’s work the restoration of the decaying

San Juan Capistrano Mission, noted that every St. Joseph’s Day, March 19th,

massive amounts swallows descended on the Mission and remained until they all

flew south in October. Acu, the

Mission’s bell ringer, claimed the tiny birds spent the winter in Jerusalem and

carried twigs they could rest on while flying over the Atlantic Ocean. In truth, the American Cliff Swallow

winters in South America, as far south as Argentina. The birds used to build their nests into the nooks and

crannies of natural cliffs, but found over the last few centuries they prefer

man-made walls and buildings, especially those with eves to hide under. For a long time the Mission provided

the tallest structures for many miles, thus becoming the favorite place for the

swallows to summer. The story of

the swallows return to Capistrano was published in a book few people noticed,

but one of them was an editor for the Los Angeles Times named Ed

Ainsworth. Through the early 30s,

Ainsworth would call up the Mission on March 19th to see if the

swallows had indeed returned, they’d say- yes, all the birds are here and

accounted for- and Ainsworth published the quaint story in his column. The newspaperman never bothered to

actually go see the event until 1936 when he got a call from an national

broadcaster who said they wanted to put on air this miraculous migration of

animals acting like clockwork. A

little worried that he put his reputation on the line for an event he’d never

witnessed, Ainsworth sped down to Capistrano to see Father Arthur Hutchinson,

who said- well, the swallows more or less arrive around St. Joseph’s Day, but they

didn’t necessarily arrive on a single day, there were no guarantees, these were

animals after all. With crowds on

the way, ready to watch the skies, and big time broadcasters showing up looking

to fill airtime, and Lord only knows where the heck the swallows were,

Ainsworth and Hutchinson did all they could do: they prayed.

|

| Swallow's nests in the eves at Mission SJC |

On March 19th, the

equipment was set up, two thousand people were in attendance, the governor had

even shown up, and there were no birds.

The clock ticked, people wandered about the quite little town, surely

the busiest day the shops and restaurants and bars had ever seen, Ainsworth and

Hutchinson began to sweat.

Just as people began to give it up and head home, a cry went up that a

massive black cloud appeared to the south. The complaints and jokes suddenly ceased as every head

tilted up. The largest flock

anybody had ever seen poured into the town, zipping about, catching bugs and

building nests on the high mission walls.

The radio broadcaster reported the “skies were blackened with swallows.” The next morning the return of the

swallows to Capistrano made national headlines and the legend was secure,

establishing a tradition that on every March 19th the people of San

Juan Capistrano invited to world in for celebrations and parades. Even in the

sad state of disrepair it was it in, the Mission, by providing a home for the

swallows, would provide the means for putting Capistrano on the map for a

second time.[12]

One of the businesses visitors

surely frequented on that big day in 1936, was a small bar only about a eighty

yards from front door of the Mission, called El Traguito. The name literally means “Little

Swallow”, but is a rather clever play on words because, just as in English, the

swallow being referred to can mean the bird, but also the sip of a drink. All I could find about this bar with a

great name war that it open some time in the late 20s and mostly served the

vaqueros and field workers from the nearby ranches and groves. In due time, this bar would become the

legendary Swallow’s Inn Saloon.[13]

In the October of 1776, George

Washington, friend of the show who saw buying votes with bumbos back in Episode

Zero, was off to a rocky start to the American Revolutionary War, but roughly

3000 miles and a whole world away a small band of Indians, a few soldiers and

two Franciscan priests broke ground on the seventh mission in Alta California

and the first permanent man-made structure in what would one day be Orange

County. Many years later a book

would be found in the Mission with a scrawling in the margin by one of the

Spanish missionaries that read, “I have this day prayed for the success of Mr.

George Washington whose cause seems to be just.” One of the soldiers present at the beginning was Lt. Jose

Francisco de Oregta, who was charged with scouting and mapping the area and

whose name today is everywhere around San Juan, gracing everything from a windy

mountain highway to animal hospitals.[14]

There were a number of different

native tribes in the area, but the largest in San Juan were called the

Acagchemem, which, according the tour you can take at the Mission, translates

roughly as “the people who sleep in piles.” Today, the Acagchemem, along with a few other tribes of the

area, most often refer to themselves the Juaneno, which, as you can probably

guess, takes the Spanish name from the Mission. Obviously, the Mission impacted the native people greatly,

and by their estimation not entirely negatively, as Juaneno is the name they

prefer. As I said, friars in San

Juan did not need to bribe or imprison the Juanenos into becoming neophytes, as

the promise of baptism enticed more natives than they could even house. However pleasant the Juaneno and Franciscan

relationship appears to have been in many repects in Capistrano, local

historian Pamela Hallen-Gibson mentions early troubles in reigning in the

sexual proclivities of some of the Spanish soldiers. I have largely ignored the military prong of the

colonization effort thus far, but many of the low level soldiers who were there

to protect the missions were in fact criminals from the mainland of New Spain

who were serving out their sentences with mandated military duty in this

desolate backwater. It is

unsurprising then that there would be cases for rape and prostitution between

the guards and the people they were theoretically protecting. Apparently, in the first three weeks of

the Mission opening, while Farther Presidente Serra himself was still in

Capistrano, some soldiers were executed for indecent activities and a local

chief was punished for basically acting as a pimp for the soldiers. The major takeaway from the incident

lies not that the crimes occurred, but in that the officers and padres made

examples of the offenders by punishing them so severely and swiftly. A far greater threat than the actual

soldiers to the native population was the introduction of syphilis, which along

with dysentery, persisted to be the leading killer of the neophytes.[15]

There is some good archaeological

evidence that suggests the original San Juan Capistrano Mission had to be moved

in it’s early years, probably due to problems with the water supply, but nobody

is quite sure from where from and, since the friars oddly made no record of it,

we’re not sure if it happened at all.

The points for debate are numerous, detailed and unsatisfyingly

inconclusive, so I’m not going to spend time on it, but just know that the

Mission we have known and loved might be just a tad younger than that 1776

birthday. In 1806, one of the

largest buildings in California was completed in the massive stone church at

the Capistrano Mission, prompting massive multi-day fiesta in the growing town,

but an earthquake only six years later collapsed the church, killing more than

forty people inside. The destruction

wrought by the earthquake can still be seen today, with the ruin just a shell

of the short-lived magnificence that fell over 200 years ago.

|

| The ruins of the old chapel today. |

The community around the Mission

remained peaceful and almost completely self-sustaining, if never wealthy,

throughout the Spanish era. On of

the more famous events was the raid on the Mission by the dread pirate

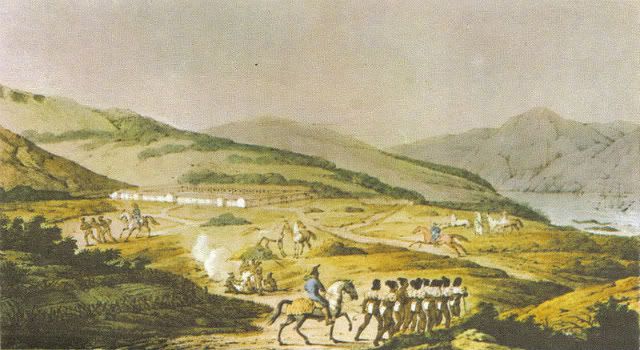

Hippolyte Bouchard. In 1818,

Bouchard pillaged his way down the California coastline and finished off by

anchoring at Doheny Beach and sending his men into San Juan Capistrano to clear

out everything that wasn’t nailed down.

Legends emerged a Pirates of the Caribbean style attack on the

defenseless town, with paintings of rabid swashbucklers gorging themselves on

wine, plundering the Mission’s meager positions, as the helpless frays could do

nothing by kneel and pray for deliverance. Like most rowdy pirate stories, this is only a half of the truth. Bouchard was actually not a pirate, but

a privateer, which is pretty much just a pirate for hire. None the less, rather than sailing

under the “black flag”, the French sea captain’s ships waved the flag of United

Provinces of Rio de la Plata, a newly independent nation that would eventually

become Argentina and was at war with Spain in 1818. Bouchard plundered with a purpose in California, only

attacking property directly held by Spain, so that he could bring back funds to

South America for the war effort.

Rather than sneaking in the dead of night, Bouchard sent emissaries to

the Mission and kindly requested he be given food and water for his voyage

home. Even if it was the type of

kindly request made when both parties know who has the cannons. No matter how low on supplies the

Mission may have been I have to wonder at the wisdom of the senior officer, a

man named Santiago Arguello, who told Bouchard they could give no edible

supplies, but offered a small amount of powder and shot. The next morning 140 men and two cannons

marched from the beach to the Mission and were only briefly met by Arguello and

his soldiers on horseback who fired a couple shots and made for the hills,

where they remained until the pirates finished looting. One of Bouchard’s commanders wrote

this, “We found the town well stocked with everything but money and destroyed

much wine and spirits and all the public property, set fire to the king’s

stores, barracks and governor’s house, and about two o’clock we marched back

through not in the order we went, many men being intoxicated, and some were so

much so that we had to lash them to the field pieces and drag them to the

beach, where, about six o’clock we arrived with the los of six men. Next morning we punished about 20 men

for being drunk.” Of these six men

who did not return, according to historian Jim Sleeper, were the first Anglo

and black residents of Orange County.[16]

In 1821 Mexico gained

independence from Spain, but the young nation’s hands were too full with

revolts and internal strife for at least a decade for anyone to pay real attention

to California. The Franciscans,

seeing little change in their original task, continued to expand, building the

last Mission in Sonoma in 1823. However, as the republican government settled

in to Mexico DF they began to institute progressive policies, such as outlawing

slavery in 1829 and the Secularization Act of 1833, which emancipated all

Indians in California, gave them full Mexican citizenship and had designs to

help natives become manage their own pueblos outside the Missions. On the face of things, the policy

appears as a great and liberal idea, but the unfortunate reality of

secularization just led to uncertainty and new opportunities to

exploitation. First, upon

emancipation many of the younger neophytes simply left, weakening the

communities’ labor force. Even in

San Juan, known for good relationships with the natives, there was enough resentment

that a minor rebellion ensued in 1821 when news arrived of Mexican

independence, in which they demanded the arrest of the senior friar. They jumped the gun by a good decade,

but when true freedom became an option, many jumped at the chance. In 1834, ten missions, including San

Juan, had their property seized by the government, half was given to the

neophytes, half would be administered by the governor. Guess who got the better half of

things? The governors tracks were mainly

sold off or given to prominent men as gifts. The Indian half in San Juan was managed by a superintendent

who $1000 a year salary would be paid by the people of the pueblo, establishing

a kind of modern feudalism. In 1838,

the superintendent position went to Santiago Arguello, the same soldier who,

twenty years earlier, refused dread pirate Bouchard’s demands and then abandoned

the town and mission at the privateer’s mercy. Arguello acted as if a duke and Capistrano was his fiefdom,

arbitrarily putting his own brand on the best animals and using Indian food,

products and alcohol to buy things for himself. Though the Juaneno community complained that their

superintendent was bleeding them dry, they could not get Arguello removed, so

again, many just left. In 1833,

their were 861 neophytes attached to the mission according a census, in 1840

there were only 60 remaining, living in poverty in a failed pueblo.[17]

It was during these struggling years that San Juan got one

of its most famous visitors, Richard Henry Dana. Dana came from Massachusetts, his family were old colonial

American stock dating back to the 1640s, he studied under Ralph Waldo Emerson

and was at Harvard law school when a case of measles almost took the young

man’s eye sight. Spooked that he

needed to see more of the world before he saw nothing more at all, Dana signed

on as a deckhand, just another lowly sailor, aboard the merchant ship, the Pilgrim. His subsequent memoir, Two

Years Before the Mast, not only chronicled horrible conditions in which

sailors lived, but gives us a rare outsider’s perspective of California in the

Mexican era. Although the well-bred

New Englander was often conceding to the Californio culture, his descriptions are

a trove of information. For

instance this passage, “The Californians are an idle, thriftless people, and

can make nothing for themselves. The country abounds in grapes, yet they buy

bad wines made in Boston and brought round by us, at an immense price, and

retail it among themselves at a real (12.5 cents) by the small

wine-glass.” Dana also points out

that despite being a country rich in cattle hides, the Californios send every

hide east for manufacturing. So rather

than making shoes themselves, the leather must go around Cape Horn twice before

a man wore shoes made of this own leather. Due to the feudalistic style of governance, there was almost

no economy in California; hides of cattle served as currency more than actual

money. Cows were so abundant that

whole herds were skinned for their hides while the rest of the animal was

simply left out to rot. The rich dons

traded hides and tallow for any items made outside California, and the poor were

little more than serfs whose meager needs were supplied by their wealthy patrons. Dana says as much after visiting

Monterey: “Among the Mexicans there is no working class; (the Indians being

practically serfs and doing all the hard work;) and every rich man looks like a

grandee, and every poor scamp like a broken-down gentleman.”[18]

As you might guess, Dana did not particularly care the whole of California,

except for the Capistrano area and the steep cliffs that would one day bare his

name with Dana Point. He called

it, “the only romantic spot on the coast.” He occasionally admires simple and slow pace to life the

natives in the area seemed to enjoy and admired the high and white Mission

walls from afar, but he never made it to the Mission itself. On last quote I’d like to read from

Dana is his description of race and hierarchy in California, he writes, “Their

complexions are various, depending- as well as their dress and manner- upon

their rank; or, in other words, upon the amount of Spanish blood they can lay

claim to. Those who are of pure Spanish blood, having never intermarried with the aborigines,

have clear brunette complexions, and sometimes, even as fair as those of

English women. There are but few

of these families in California; being mostly those in official stations, or

who, on the expiration of their offices, have settled here upon property which

they have acquired; and others who have been banished for state offences. These

form the aristocracy; intermarrying, and keeping up an exclusive system in every respect.

They can be told by their complexions, dress, manner, and also by their speech;

for, calling themselves Castilians, they are very ambitious of speaking the

pure Castilian language, which is spoken in a somewhat corrupted dialect by the

lower classes. From this upper class, they go down by regular shades, growing

more and more dark and muddy, until you come to the pure Indian, who runs about

with nothing upon him but a small piece of cloth, kept up by a wide leather

strap drawn round his waist.

“Generally speaking,

each person’s caste is decided by the quality of the blood, which shows itself,

too plainly to be concealed, at first sight. Yet the least drop of Spanish

blood, if it be only of quadroon or octoroon, is sufficient to raise them from

the rank of slaves, and entitle them to a suit of clothes- boots, hat, cloak, spurs, long knife, and all complete, though coarse and

dirty as may be,- and to call themselves Espanolos, and to hold property, if

they can get any.”[19]

This was the era of the Dons, who

were nothing less than nobility in California. Rather than Castilians, as Dana calls them, historians today

usually refer to this upper, Latin descended, class as Californios. Throughout the 1820s, 30s and 40s,

California remained a loyal territory to Mexico City, but in this period the

people born and raised in California, got used to running their own

affairs. This is the era of

families with names that grace so many cities, streets, and neighborhoods today

throughout the state- names like Castro, Pico, Alvarado, Peralta, Carrillo, Sepulveda

and Vallejo. This is the romantic era

that inspired the Johnston McCulley’s pulp fiction novels starring Zorro, in

which the wealthy Don Diego de la Vega dons a mask and sword to defend the downtrodden

native people and once proud Franciscans against the greedy land barons of his

own class and the abusive and brutish soldiers. The first book is actually titled the Curse of Capistrano, which partially takes place at our fair

mission. By the way, there are

plenty of places you can read the ebook online, but you can listen to that book

for free at librivox.org. McCulley

can’t be counted on for any historical or geographical accuracy- like at all-

but the stories are fun and they light up the imagination, adding some life to

the Californio era that you don’t get in history books.

In San Juan Capistrano, the don

who finally set the town on a path to prosperity has the unlikely sounding name

of Don Juan Forster. An Englishman

by birth, John Forster came to Southern California for work with his uncle and

fell in love with the place. He

took Mexican citizenship and married the sister of the future governor, Pio

Pica, imminently making him one of the foremost men in the state. I had planned on using Forster as a way

introducing the conflicts leading up to the Mexican-American War of 1846, as he

was present at some key events and witnessed battles prior to the war when

Californios tested their the limits of their autonomy from the Mexican

government, but as usual, I’ve run on much longer than I expected to. I promise there will be an episode soon

that covers the military campaigns and politics that led to the American

annexation of California. The cast

of characters is too colorful and the events are too weird to ignore this

story.

For now we’ll speed things up, so

we can talk at least a little bit about the bar. Remember when you thought this episode was about a bar? As I eluded to last month, there is a

painfully small amount of information available about the history of the

Swallow’s Inn- which is fine with me because I had more than enough to say on

other matters. But the saloon,

aside from close proximity to the Mission and connection with the return of the

swallows- during the annual Swallows Day Parade, the bar is thee place get your

day time drunk on- there is a connection to Don Juan Forster. Forster set up a ranch during the 1830s

northeast of the Mission and began buying up land. He was appointed justice of the peace of the San Juan

Capistrano in 1845. At this time,

the rundown town had permanent residents hardly above the single digits and a

reputation as a great place to stop and get your day-time drunk on, with a fair

amount of prostitution to boot.

There were no friars at the mission and bands of thieves regularly came

riding into town, whampin’ and whompin’ every living thing within an inch of

its life. So Forster and a man

named James McKinnly simply bought it the Mission for $710 at an auction. The purchase that included the San Juan

Mission became Rancho Mission Viejo.

Like many of the rancheros of this era, over time Rancho Mission Viejo moved

on from cattle to become a real estate company and investment group in the

twentieth century. The money made

raising cattle paled in comparison to the money to be made in raising homes and

selling the dream of easy, sunny Southern California living. The sleepy little towns in the area,

once separated by ranchland and orange groves, slowly blended into each other,

connected first by housing tracts at the mid-twentieth century, and then by

gated communities with opulent mansions by the twenty-first. The wealthy Forster family remained

influential in the area (for instance, I went to Marco Forster Jr. High, named

after one of Don Juan’s sons), as did the families of the O’Neill’s and the

Floods who purchased Rancho Mission Viejo in 1882. Today, most people refer to the Rancho Mission Viejo group

as “The Ranch”, despite their current ranching operations being done for mainly

nostalgic reasons. Among the many

properties and business The Ranch owns is none other than the Swallows Inn

Saloon.[20]

The bar’s current residence was originally built as adobe house

built in the 1930s, while El Traguito opened across the street. According

to an environmental design firm that did a historical survey a couple years

ago, the bar moved into its current location in 1967. I also got a hold

of a 1971 interview from the local library with Elizabeth Forster, who had

spent most of her life in the area and married into the distinguished Forster

family. She mentions the buildings that housed both the old and

current locations of the bar being owned by the Forster family at some point,

but through most of the 50s and 60s the bar was owned by an Irishman name Burke

and prior to the move it was called Burke’s Tavern. On another

interesting note Mrs. Forster, having spent decades as a teacher, was able to

remember a time during the 1920s and 30s in which the majority of students

still spoke Spanish as a first language and many were often only enrolled for a

season. There were many families who constantly migrated around the state

according harvest seasons, and the children themselves would work as pickers in

the walnut groves while in San Juan. Speaking to the rapid growth and

change of the area, by the early 70s, Mrs. Forster said she hardly heard

Spanish spoken at all in school halls.[21]

Apparently the move and name change of the bar occurred so that

this Irishman, Burke, could serve Mexican food, which he called Spanish Food.

When you look at pictures Camino Capistrano from the 60s the street is

lined with signs that advertise Spanish food, which was common, as most Anglo

Americans of that era would not have stopped to eat burritos, tacos and tamales

if had been labeled properly as Mexican food. At some point, though

the kitchen at the Swallows closed to make room for a small stage and a dance

floor. The bar and stage are featured prominently Clint Eastwood’s 1986

military classic (?), Heartbreak Ridge. The movie is unwatchablely

bad, as Eastwood unleashes a flurry of jaw punches and homophobic quips, on a

mission to prove Marines are tired of being treated as second-class citizens.

The scene at the Swallow’s Inn involves a young Mario Van Peeples

moonwalking and lip syncing a heavy metal, rap, new wave, smooth jazz number as

weathered Clint Eastwood looks on and contemplates end of Western Civilization.

Nonetheless, thirty years later, the bar looks exactly the same.

Most of the old timers at the Swallows who spoke with me on my

last visit were friendly, but a bit weary of a stranger showing up with a

digital recorder and saying I was working on something called a podcast.

It was confirmed that I was up to something fishy the moment I produced

academic release wavers and nobody felt like discussing bar history anymore,

instead referring me to walls filled with pictures of regular customers and

bartenders. Obviously, my explanation of who I am and what I’m doing

needs some fine-tuning. Next I visited the San Juan Capistrano

Historical Society in the gorgeous restored O'Neill house alongside the train

tracks, but their folder labeled “Swallow’s Inn” contained only a single

article from the Orange County Register from 1978, in which a group of homesick

Texas expressed surprise and comfort finding a “hard-core, country-western bar”

in the Swallow’s. The article also explains the rules of frozen duck

racing, a popular Swallow’s tradition in which participants fasten shot of

booze to a frozen fowl and attempt it tow it across the bar without spilling.

When it comes down to it, the Swallow’s Inn never did anything

special to secure its legendary status in the minds of residents of South

Orange Country. No patrons with

long and illustrious literary careers, no scandalous stories that hint to a

secret history of the Southland, no role in the continued existence of our

democracy, but there is a feeling to the place, like a lost pocket of the Old

West. Not a touristy recreation,

but like those rare occasions you see somebody wearing cowboy boots and they

don’t look like an asshole. A few of

the old timers recalled a hitching post out front that was used somewhat

regularly despite the streets being long since paved, and on crazy nights it

wasn’t super surprising to see somebody ride one of those horses in the front

door and out the back, off into the night in the direction of the 5 freeway. I can even remember sawdust covering

the floor when I first actually had a drink there in the 90s. So the saloon has the air of an organic

confluence: the once rowdy and rural with the raising mundane and

suburban. It’s places like these

that make people like me yearn for the past. Not because the past was simpler, but because it was so

different and foreign. It’s places

like these that remind us that every day we live amongst and constantly tear

down the vestiges of fading civilizations. Since Gaspar de Portola and Juan Crispi first walked from

San Diego to Monterey, California has been a place of exponentially rapid

change, only occasionally pausing to remember to preserve something before it

fades from memory.

Thank you for downloading this episode of the Bear Flag Libation.

This week I want to thank Gwen at the San Juan Capistrano Historical

Society for generously giving me lots of material on the wider story of city,

even if we were mostly unsuccessful at finding material on the Swallow’s.

Also, thank you to Tony and Joanna Lioce and Sue Fimbres, who all attempted

to help put me in touch some people who might know some of the earlier history

on the bar, even if we were mostly unsuccessful in finding material on the

Swallow’s. And finally thanks to my mom, Luanne Burton, who visited a

number of the city’s bureaucratic offices for me on a hunt for information,

even if we were mostly unsuccessful in finding material on the Swallows. As usual, thanks to Anthony Lukens, who

is always successful in playing the Creedence for our theme song. The two versions of the song “When the

Swallows Come back to Capistrano” you’ve heard are by Pat Boone and Glen Miller,

respectively.

Every time I make promises concerning the scheduling of future

shows, I end up breaking said promises, so the next topic will be on California

history and it will come out when it is done. Please feel free to give me any feedback at bearflaglibation@gmail.com, or leave a comment the show page at

bearflaglibation.blogspot.com.

Don’t forget to become of fan of the show on the facebook page at

facebook.com/bearflaglibation.

Beyond posting pictures and notifications that have to do with episodes,

I post links and articles that fans of the show would find interesting. And I’m also going to start posting

“California Dive Bar Juke Box Song of the Week”, which will not just be a great

song by a Golden State artist to play in a bar, but I’ll be providing a bit of

history for you to impress and/or bore your friends with. Enjoy your warm winter, friends, and

drink Mexican beer.

[1] Edward

Everett Hale, “The Queen of California,” Atlantic

Monthly 13, no. 77 (1964): 265–279.

[2] William S. Simmons, “Indian Peoples of California,” California History, Vol. 76, No. 2/3,

(Summer - Fall, 1997), 49; Kevin Starr, “California: A History” (New York:

Random House, 2005), 13.

[3] The Diaries

of Fray Juan Crispi and Gaspar de Portolá on the days of July 23rd

and 24th 1769, published on the website of the Pacific Historical

Society,

http://pacificahistory.wikispaces.com/Portola+Expedition+July+24%2C+1769+Diaries,

accessed on December 15th, 2013.

[4] Pamela

Hallan-Gibson, Dos Cientos Anos en San

Juan Capistrano (Orange, CA: The Paragon Agency, 2001), 11-12.

[5] Brian A. Aviles and Robert L. Hoover, “Two Californias,

Three Religious Orders and Fifty Missions: A comparison of the missionary

systems in Baja and Alta California,” Pacific

Coast Archaeological Society Quarterly 33, No. 3 (Summer 1997), 10-38.

[6] Aviles and Hoover, “Two Californias”, 16-21.

[7]

Hallan-Gibson,

Dos Cientos Anos, 12-16; Russell K. Skowronek, “Sifting

the Evidence: Perceptions of Life at the Ohlone (Costanoan) Missions of Alta

California,”

Ethnohistory 45, No. 4

(Autumn 1998), 681, 691.

[8] Skowronek, “Sifting the Evidence”, 691, 697.

[9] Edward D. Castillo and Lorenzo

Asisara, “The Assassination of Padre Andrés Quintana by the Indians of Mission

Santa Cruz in 1812: The Narrative of Lorenzo Asisara,” California History 68, No. 3, (Fall 1989), 116-125.

[10] Francis F.

Guest, “An Inquiry Into the Role of the Discipline in California Mission Life,”

Southern California Quarterly 71, No. 1 (SPRING 1989), 4-5.

[11] Guest, “Role

of the Discipline,” 8-10.

[12] “Biological

Sensitivity Assessment, Historic Town Center Master Plan, San Juan Capistrano”,

a study conducted by the Templeton Planning Group of Costa Mesa, California. “

Dated for May 2011. The Swallow’s

Inn is mentioned in section 5.5-16.

Found at, http://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=2&ved=0CDcQFjAB&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.sanjuancapistrano.org%2FModules%2FShowDocument.aspx%3Fdocumentid%3D25010&ei=9WHUUp3DN4XvoATVkYLgAg&usg=AFQjCNFfUXxNOS3udutTqzQcUBT0u2ybyQ&sig2=0J8qaz2DehnWIvG4fUVmeQ&bvm=bv.59026428,d.cGU, accessed

January. 10, 2014.

[13] Hallan-Gibson,

Dos Cientos Anos, 102-104.

[14] Hallan-Gibson,

Dos Cientos Anos, 9.

[15] Hallan-Gibson,

Dos Cientos Anos, 16; Harry Kelsey, “The

Mission Buildings of San Juan Capistrano: A Tentative Chronology”, Southern

California Quarterly, Vol. 69, No. 1, Spring 1987, 24.

[16] Hallan-Gibson,

Dos Cientos Anos, 19-20.

[17] Hallan-Gibson,

Dos Cientos Anos, 25-27.

[18] Richard

Henry Dana Jr., Two Years Before the

Mast: A Personal Narrative (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1911), 92-94.

[19] Dana, Two Years, 170, 95-96.

[20] Hallan-Gibson,

Dos Cientos Anos, 27-30; Rancho

Mission Viejo website, http://corp.ranchomissionviejo.com/community-development/investment-properties/,

accessed on January 5, 2015.

[21] “Historic

Town Center Master Plan”, 5.5-16; Interview with Elizabeth Forster by Suzanne

Jansen on July 26, 1971, conducted as part of the CSU Fullerton Oral History

Program, accessed at the reference desk of the San Juan Capistrano Public

Library.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)